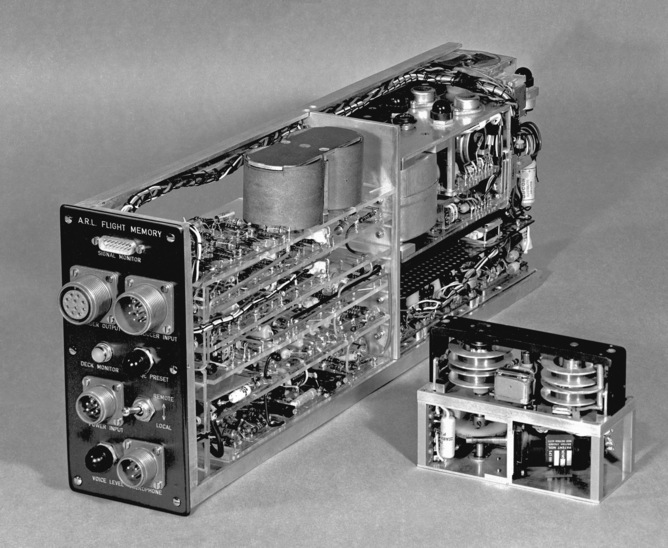

Commercial innovation in the 21st century is very focused on IT engineering and much less so on...

Ian Maxwell

The Australian Federal Government’s ‘National Innovation and Science Agenda’ was hosting the school theme of ‘Drones, Droids and...

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, Patrick Vlaskovits has decided that the quote below, attributed to...

Some time back I wrote a paper outlining one hypothesis as to how the corporations in the...

A couple of weeks back, on the occasion of my daughter’s impending birthday, I was wandering through...

Studies and anecdotal reports suggest that having a mentor is crucial in developing your career. The state...

Ian A. Maxwell is a veteran Technology Entrepreneur and Venture Capitalist. He is currently CEO ofBT Imaging,...

Ian Maxwell has a slightly tongue in cheek proposal for Crowdfunding originally published on his blog. In...